Learning patience from Deng Xiaoping

How the Chinese leader's life helped me overcome the FOMO of being late to the party

My first job out of college was joining Lyft as an Associate Product Manager (APM). My cohort was a uniquely old class of new grads given we averaged 24 years of age due to gap years and extended programs. One of the Lyft APMs told me that she felt discomfort starting her first job out of college two years later than most people because she had always been ahead of her peers in her life. Just this 2-year “delay” was enough to bring her stress, and could I blame her? We’re surrounded by ambitious go-getters who have consistently been ahead of the pack, skipping grades and accelerating credits. Modern mass communication has made it much easier to ogle at how the other half lives and easier to feel left behind. So we see celebrities going global at 17 or college roommates married with kids right after commencement. All of this reminds the leftovers that others have reached these societal life milestones before you did. Working in tech, the sense of youthful ambition is even more palpable. The legends of Mark Zuckerberg, Evan Spiegel, and Alexandr Wang are the heroic war stories traded in the camps of Silicon Valley. The self-made billionaires keep getting younger and they keep finishing less of their bachelor’s degree! These tech moguls became limitlessly wealthy before some of them were of legal drinking age and thus they have the rest of their lives to indulge in their success, ranking them above the lame old-school titans of industry who made their wealth in a typical course of human life. Why be old and rich when you can be young and rich?

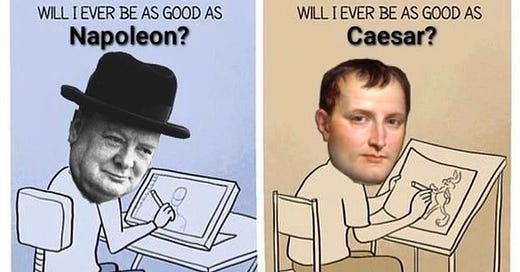

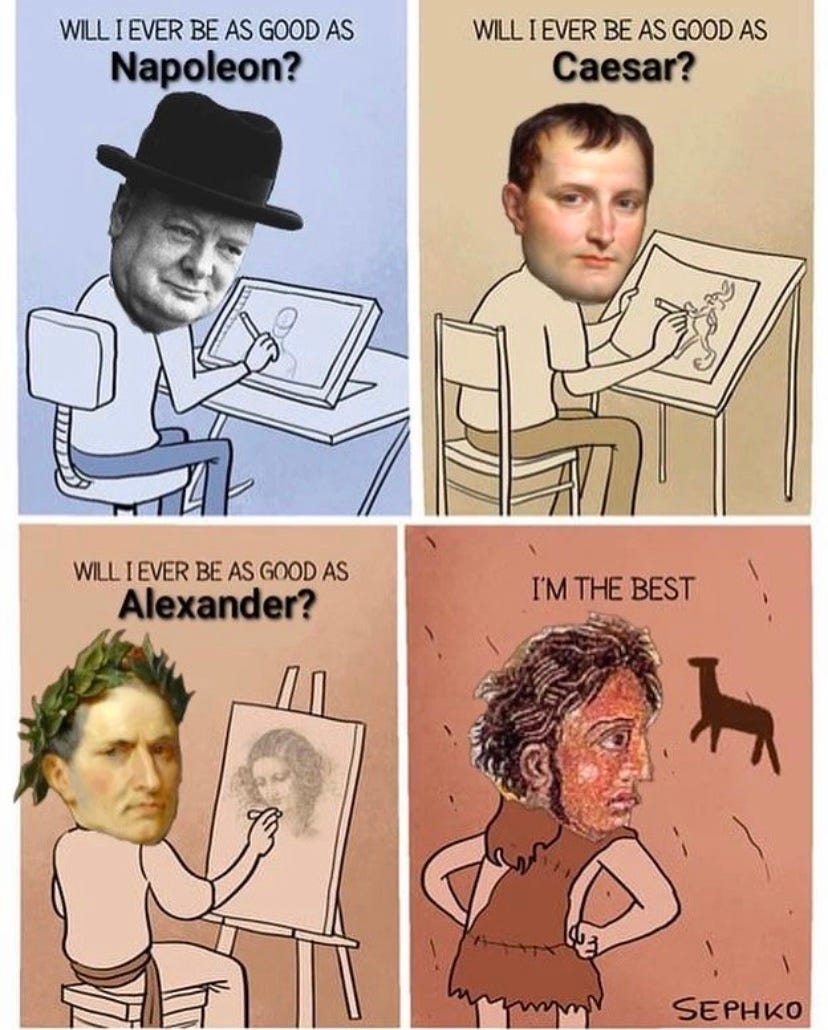

Reading history I was seeing even more great figures accomplish so much at such youth. There is 海子 (Hai Zi) thecontemporary Chinese poet who attended China’s most prestigious university at age 15 and was active only for 4 years from 21 to 25 before his tragic suicide but left an indelible imprint on his generation. At age 17, Évariste Galois solved a 350-year-old open problem and defined a new field of mathematics that today is still considered advanced and hard to grasp. And then there’s Alexander Hamilton who was a founding father of the United States of America at the ripe age of 20. A large portion of what I know about Hamilton is from Lin-Manuel Miranda’s musical so please forgive me if the historicity is lacking but in the musical there is a number that included the lines “Why do you write like you’re running out of time”. Hamilton lived with a sense of unnatural urgency as if he was racing against a deadline to make something out of a life that didn’t give him much to start with, and to that end he succeeded, being commemorated on the ten-dollar bill to this day as the first Secretary of the Treasury. (By pure coincidence these three figures all died of unnatural causes. Galois and Hamilton by duel and Hai Zi by suicide on train tracks).

When I started reading Harvard Sinologist Ezra Vogel’s seminal biography of Deng Xiaoping (Deng Xiaoping and the Transformation of China), these feelings of being late to the game exacerbated once more. Like many early Chinese Communists, Deng was foreign educated. Along with later CCP leaders Zhou Enlai, Nie Rongzheng and Chen Yi, Deng was sent to France under the Dilligent-frugal Work-study program at the age of 15 in 1920. It was a program originally set up by Chinese anarchists to educate young Chinese in Western science and culture while cultivating in them a work ethic and empathy for labor through their own work in factories. Many of them radicalized as Communists in France and Deng was no different. He became active in political organization at age 16, giving speeches, printing pamphlets and proving himself as a leader by the time he joined the Chinese Communist Party in Europe at age 19. When I first read of this, I looked upon my own life’s progress in despair. I was 25 years old and at my age, Deng had 9 years of political experience under his belt. This isn’t to say that I’m planning to have a political career but more of a lament that not only did he find his calling at such a young age, he already had made 9 years of progress on his life’s work by the age I’m reading about him. (He left home at age 15 and never returned because his dedication to China always came first).

So was Deng just another example of youthful achievement like Alexander the Great and this yet another “and Caesar wept” moment in my life? I thought so until I read further into the book. The work of nation building is filled with trials and tribulations, especially the life of a revolutionary trying to build a radically new society. The dangers accompanying power in CCP politics were so well known that reformist premier Zhao Ziyang had to be convinced to join the central government in Beijing because he was worried that no one close to power ended up well. Despite an early start, Deng’s life was far from smooth sailing with a linear trajectory upwards. He was thrice purged from power, the second time in 1969 lasted a full 8 years where he was sent to the Jiangxi countryside and his son was tortured to the point of paraplegia during the Cultural Revolution. During his time in rural Jiangxi, he didn’t wallow in despair as some of his peers did. China’s first foreign minister and first mayor of Shanghai Chen Yi (a fellow student of Deng’s in France) reportedly died in depression as he bemoaned his treatment and the end of his career. Deng instead read and wrote and thought intensely. He would take long walks in the fields after his labor, contemplating the problems with China, the issues with the system, and what he would do when he came back to power so he always had a plan for day one back in office. And during those years he never gave up hope that he would return. He wrote to Chairman Mao, begging for the Chairman’s forgiveness and proclaiming that he had realized his errors for ignoring the Chairman’s wisdom. Eventually, his time to shine would come in 1977, a year after Mao died where he was brought back for the third and last time. He outmaneuvered Mao’s chosen successor Hua Guofeng and became the de facto paramount ruler of China by 1978. At this point, he was 74 years old. This was when he really began his life’s work that he goes down in history for: reform and opening, the monumental process to bring China out of the depths of Mao’s excesses and transform China from one of the poorest countries on Earth to a prospering and modernized stated. In 1976 when Mao died, China’s GPD per capita was $165, a 1/14th of Venezuela’s GDP per capita at the time and lower than most sub-Saharan African countries. It was not inevitable that China would develop into what it is now. Deng’s agency in this process is unmistakable as he had to wrestle against conservative party elders and a decimated populace while preserving narrative continuity for the CCP’s legitimacy.

By age 60, most people expect the bulk of their careers to be over and are looking forward to retirement and time spent with grandchildren, and Deng was known to be a good family man who doted on his offspring. By 74, there is probably more pleasure in reminiscing than looking toward the future but that’s when Deng kept good to his promise in his letters to Mao that he still had “20 years to give to the party. 20 years to give to China.” What kind of will is needed for a man to take on the burden of a gasping nation’s weight on his shoulders at an age when he should be looking back on a life well-lived?

Reading this struck me hard, because it was such a break from the accelerating contest for youthful success that I see in Silicon Valley. Opportunities in life do not all front load in people’s twenties, especially for those who care more about doing great work and leaving the greatest impact instead of optimizing for how early success can come in one’s life so that one is able to enjoy its fruits. Political views aside about the merits of his Communist mission, Deng kept doing the good work he believed in his whole life and he never gave up. This doesn’t mean he was idle or slow. He acted urgently and worked furiously since his teenage years, but he also had the tenacity to not throw in the towel till his death at 93 (also a lesson in maintaining physical health and mental acuity). For a mission as grand as nation building, there is always more to be done and patience is a key virtue Deng possessed that enabled him to outlast many of his peers. I only hope to have but a modicum of Deng’s wisdom and perseverance, to maintain the fight till the end of my days.

(Emei went to Yale but I never knew her personally. Thought her song captured the feeling of life stage FOMO but maybe the message is blunted by her also being successful at a young age)

Great piece!

I think similar mindsets of comparison cut across multiple domains, even creative ones.

As a prospective literary novelist, for many years, I was obsessed with the idea of debuting before 30 to critical acclaim. Naturally, I had a similar swathe of anecdotes to compare myself to.

In the end, I self-published my novel years after the fact, to much more humble results, but what I find particularly interesting about the craft of literary fiction is that, much like politics, it can take decades for a writer to develop into their prime.

It's a nice point of comparison to the hyperspeed of meritocratic competition we see in SV or tech more broadly (although perhaps AGI will eliminate the need for human novel-writers altogether one day!).